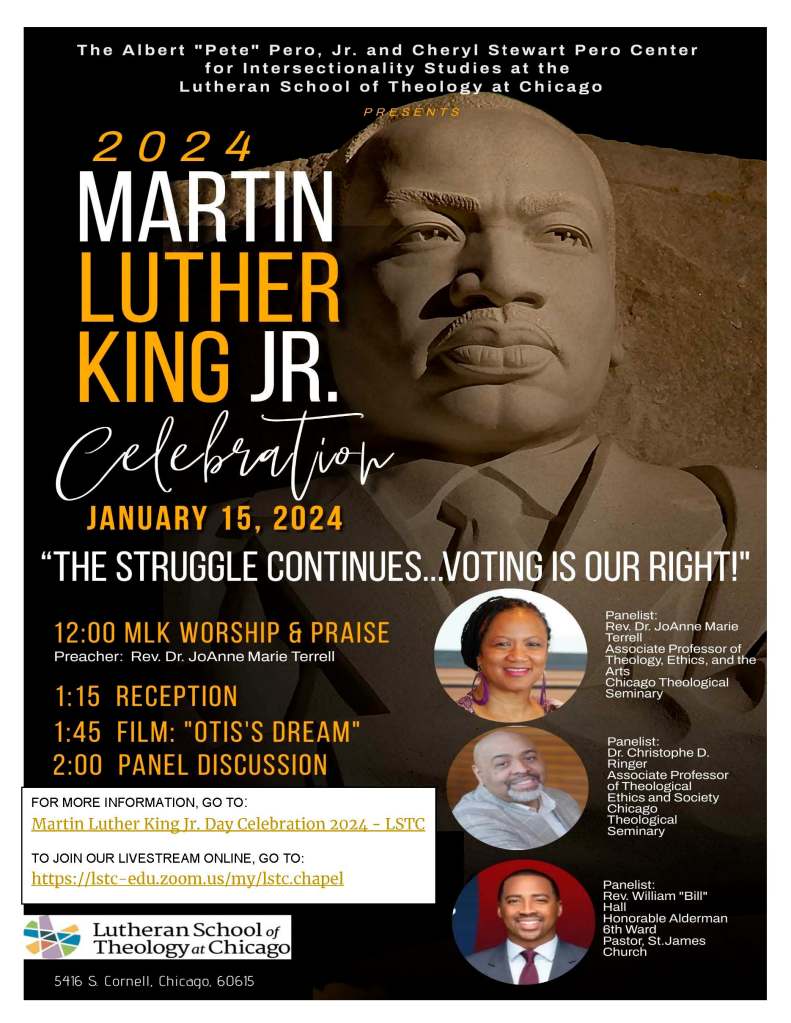

In preparation for our annual Martin Luther King, Jr. Day celebration at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago on Monday, January 15, 2024 at 12 pm CDT (click here to register), we are releasing an overview of Dr. King’s life and priorities, written by the Rev. Dr. Reggie Williams, which gives also gives some much needed historical background to the Montgomery Bus Boycott – history on how the boycott was inspired by the abuse and sexual assault of Black women, Read, comment, and share, and we’ll see you on Monday, January 15, 2024 at 12pm CDT!

Rev. Dr. Linda E. Thomas

Professor of Theology and Anthropology; Director, Albert “Pete” Pero, Jr. and Cheryl Stewart Pero Center for Intersectionality Studies

____________

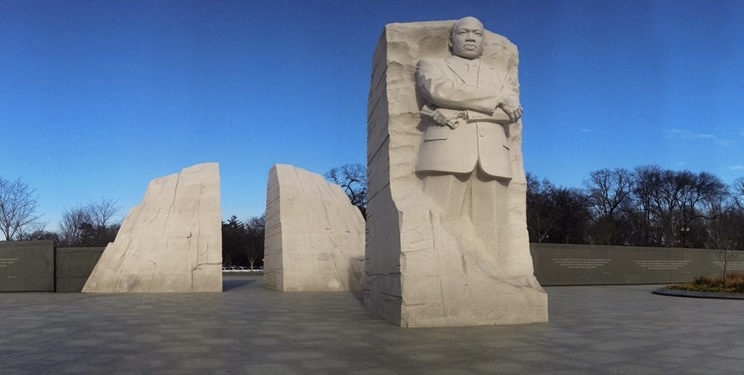

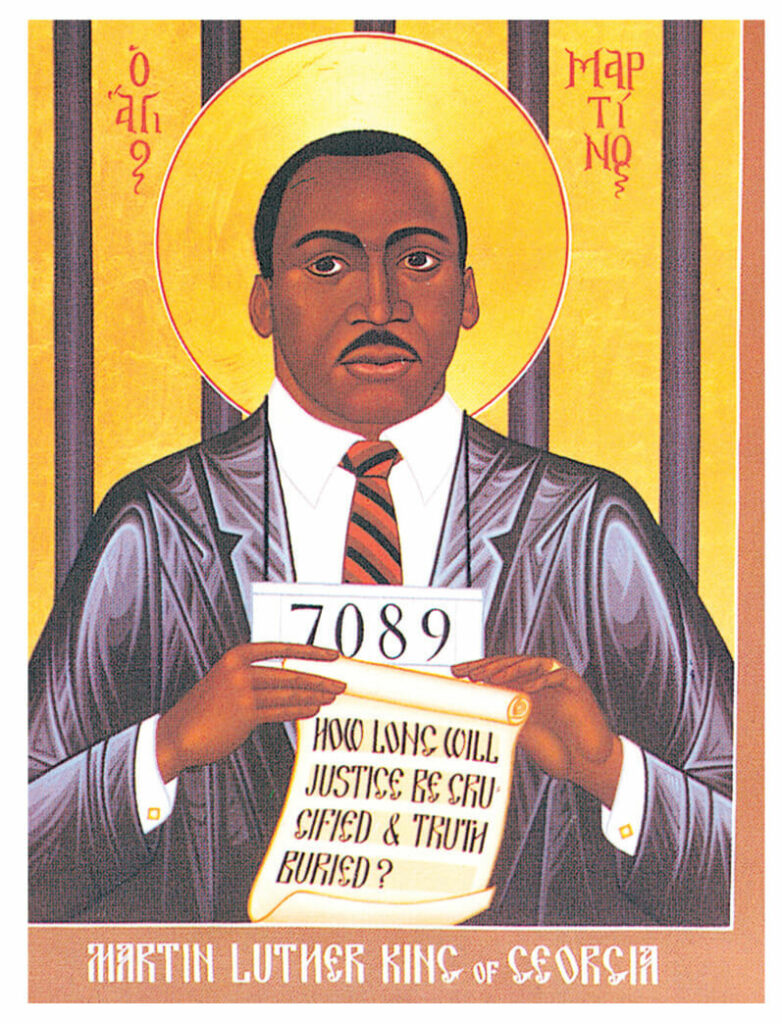

The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. remains one of history’s most significant public theologians, worldwide. Politicians and private citizens from around the world have gone to great lengths to acknowledge his history-shaping impact since he was assassinated in April of 1968. Today, he is the only U.S. civilian with a national holiday in his honor. There is a monument in the nation’s capital dedicated to him; ‘Out of the Mountain of Despair, a Stone of Hope.’ In 1964, he was the youngest-ever recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize at age thirty-five, and the second African American to receive that recognition. There are more than one hundred K-12 schools across the country that carry his name, and it is estimated that nearly a thousand streets in the U.S. alone are named for him. Dr. King is widely recognized by the recorded sound of his voice, and his legacy is invoked at the mention of a phrase, ‘I have a dream.’ He is a towering historical figure, a champion of the modern American civil rights movement.

King’s Family

He was given the name ‘Mike King Jr.’ at birth, in Atlanta, Georgia, on January 15, 1929. For reasons that scholars dispute, his father changed both of their names to Martin Luther when he was five years old. He was the eldest son, and the middle of three children, born to Michael and Albertina King: Christine King, Mike King Jr, and Alfred Daniel Williams King. At birth, he inherited a lineage from Black ancestors who knew enslavement and sharecropping, among other myriad forms of white racial terror. He had great-grandparents on both sides of his family who were once enslaved, and his paternal grandfather was a sharecropper, accustomed to debt peonage and other creative forms of abuse. For his maternal grandparents, Adam Daniel (A.D.) Williams, and Jennie Celeste Williams, education and a faith tradition that connected personal piety and social justice were core to survival in a white racist nation.

King’s family refused the allegations that whiteness made about the world and the place of Black people in it. Those assertions meant that Black people have no rights that White people are obligated to respect. They are the practical implications of a centuries-long national habituation in a bio-political organizing scheme that makes the bodies and even the families of Black people fair game as targets of White lust for ownership and domination. Whiteness is that scheme. It is a body of discourse; a species of reality that reproduces itself as timeless truth, with seeds of procreation internal to itself. Meanness is not the main trait of this ideology; it makes meaning and is productive. It populates our desires and demands our loyalty. Like parthenogenesis, it reproduces itself, by itself, as a logical narrative of human hierarchy, imparting societies with a continued obsession for White racial ascendency over everything related to earth and heaven. Whiteness is the self-sustaining ideology that makes white supremacy legible. It generates knowledge of human difference, capturing all of humanity by an account of racial types that is replete with portrayals that make the types knowable in the abstract, and arranging them as a hierarchy of being with White at the apex and Black as the nadir.

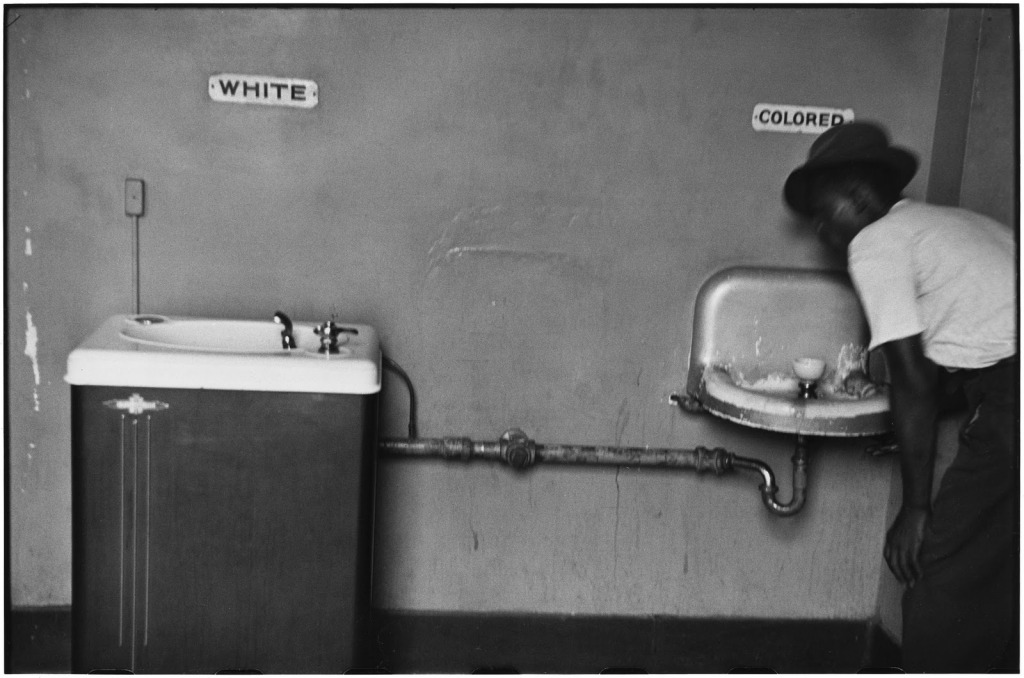

From chattel slavery to ‘separate but equal,’ whiteness is fundamentally an argument for ownership and belonging. It teaches a hierarchy of human difference for a community we should all want in the world that is based on one’s supposed ability/inability to properly possess oneself and the earth. Proper possession is a capacity that is recognized by ones positioning within the hierarchy of human difference and is key to the plot in the script of our life together. King’s family knew of this script and its implications for Black people. Whiteness includes religious ideology that recognizes Jesus as the figurehead at the apex of the hierarchy of human difference with the term ‘human being,’ or ‘fully human,’ as a hegemonic concept for whites only.

King’s Inheritance

King’s family inheritance included a Christian response to whiteness. He was raised in a tradition of Black abolitionist Christianity, within which, he was the third generation of Baptist preachers and Morehouse alumni that included his maternal grandfather, A.D. Williams, and Daddy King. His was what Gary Dorrien identifies as a Black Social Gospel; rooted in Black abolitionist religion and the teaching of the Bible that God favors the poor and the oppressed. The Black Social Gospel saw eternal salvation paired with a this-world focus on the dignity of Black people where matters like race determine social value, as the way one must think through the meaning of the gospel. This Christian protest tradition taught that God was concerned with our eternal soul, and our everyday well-being.

King’s Education

Knowledge of this history is fundamental to understanding the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. He emerged as a leader from within a Black Christian protest tradition, in a moment when the ongoing tradition of Black struggle against political evil was thrust into the spotlight by a providential convergence. In Montgomery, Alabama, the insatiable cruelty of white supremacy met with ideas for Christian resistance already present within the local Black community. Those ideas were subsequently buttressed by King’s rhetorical appeal, his take on the Black church protest tradition, and newly emerging technologies that made it possible to quickly reach a global audience with a voice, a photograph, or video footage.

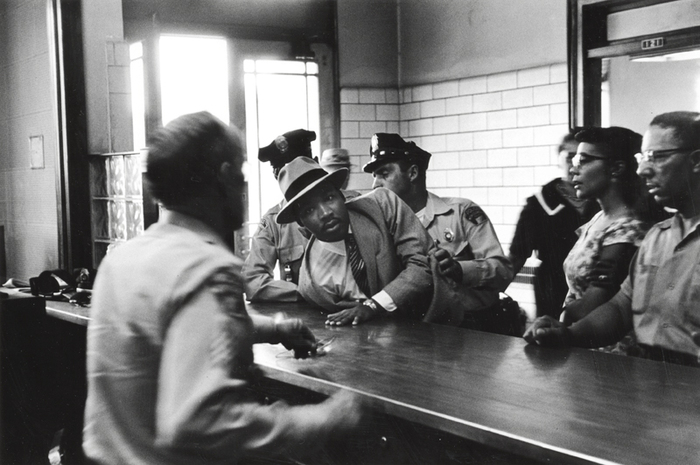

King came into public view in 1955, as a young, highly educated Black preacher from the Jim Crow south, with a penchant for Christian socio/political activism. He was the new pastor of the prestigious Dexter Ave Baptist Church, who became the prominent voice of aBlackcommunity that was undertaking what would become a successful city-wide protest against racial abuse on city busses. He arrived at his new pastorate in May of 1954. He was Dexter Avenue’s twentieth pastor; twenty-six years old, and still finishing his dissertation for a PhD in Systematic Theology from Boston University.

The Movement Starts

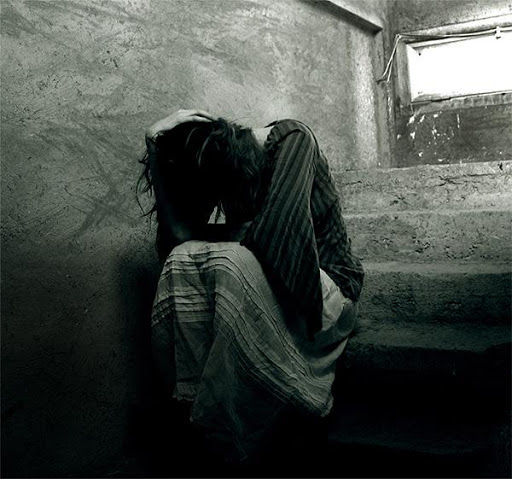

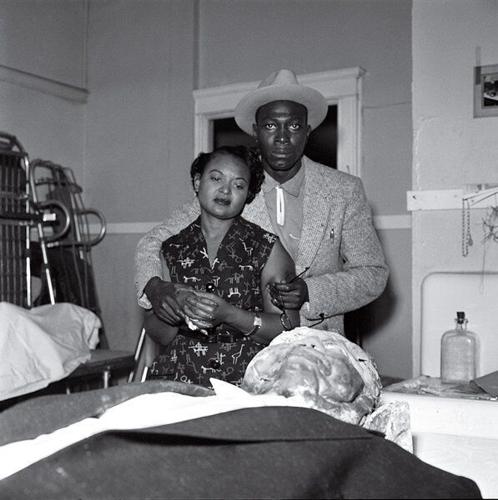

Ten years prior to his arrival in Alabama, twenty-four-year-old Recy Taylor was brutally raped by a group of white men while she was walking home from church in Abbeville, a town that is neighbor to Montgomery within an hour’s drive. Mrs. Rosa Parks, branch secretary of the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP, was dispatched to Abbeville to investigate. The assault against Ms. Taylor was widely known in Alabama, as were her white assailants. Yet, no arrests were made. Racism kept the lives of Black people within constant reach of white prurience, and outside of the moral scope of political governance.

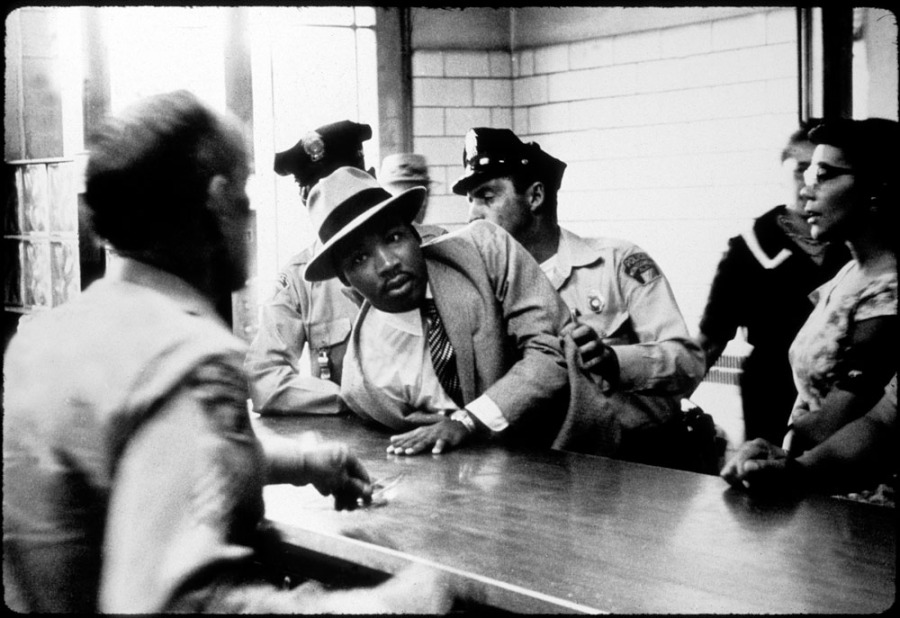

Eight years after Ms. Taylor’s assault, in 1952, sixteen-year-old Jeremiah Reeves was sentenced to death in Montgomery after police secured a forced confession from him for the alleged sexual assault of a white woman. Three years later, on March 2, 1955, fifteen-year-old Claudette Colvin was likely upset about the unjust treatment of her friend, Jeremiah Reeves, when she was physically dragged from a Montgomery city bus and arrested for refusing to comply with the bus segregation ordinance, and for resisting the police. On October 15 of the same year, Mary Louise Smith was also arrested for refusal to give up her seat to a white passenger.

Black organizational leaders had their eyes on the city busses where its primarily Black women riders were habitually mistreated. They were working on a plan to address the conditions for Black bus riders prior to these two arrests. At first glance, young Colvin’s arrest seemed to be the catalyst they’d been awaiting, until it was decided that she would not be the right person to inspire community support for a boycott. The newcomer, Martin Luther King Jr., was already organizing his church to engage in social action for justice as a matter of Christian faithfulness. But he was not yet an active participant in plans for change on the city busses.

From the Pulpit to the Public

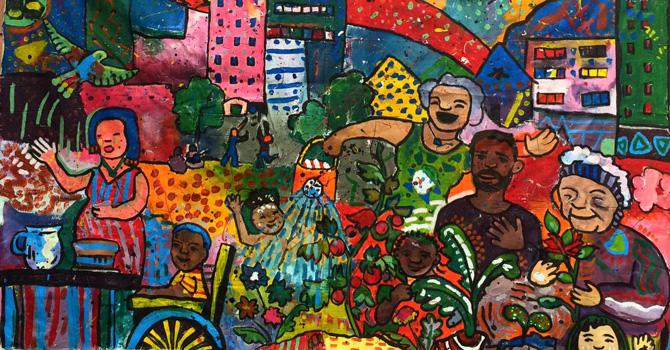

King was volunteered and voted into a key position of leadership for the protest before he could object. He rose to the challenge, helping to guide the city’s Black populace through a tender balance of direct and aggressive, yet Christian resistance, to white supremacy. The outlook that whiteness forced upon society was disrupted by a black social gospel claim of ‘God with us,’ in the struggle to build what King later called ‘The Beloved Community.’ King’s theological language of Jesus preferential option for the poor and the oppressed was a Christian assertiveness in which King advocated a revolution of values.

Accordingly, the giant triplet of racism, materialism, and militarism that caused people to value ownership, belittling personality by treating black people like things, must be transformed into an ability to respect personality, and to value all persons, blacks included, as human beings. Satyagraha, or ‘love force’ was key to this effort. It included an interpretation of the way of Jesus as described in the Sermon on the Mount, and the methods of Gandhi’s non-violent resistance.

The Montgomery movement gave Dr. King a global stage, and an international presence. He subsequently published five books: Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story (1958); a collection of most requested sermons under the title Strength to Love (1963); Why We Can’t Wait(1963); an assessment of America’s priorities and a warning that they need to be re-ordered entitled Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? (1967); and finally, The Trumpet of Conscience (1968), taken from his 1967 Massey Lectures delivered for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

His influence continues with further emphasis on the broader impact of white supremacy that is today recognized as a load bearing concept, housing multiple oppressions—racism, sexism, classism— in its practice of naming and stabilizing the racial world of the U.S. post-bellum imagination. Yet, it is also true that scholars question whether the U.S. democracy that King called to account is at all capable of being more than hegemonic, given that it was established with black people as contrast to its founders, which is to say, as non-human, and non-free, non-citizens. At the state level, the equivalent notion of “human” is the citizen, and despite King’s efforts to make those concepts, human and citizen, broad enough to include black people, scholars are doubtful that they can be legible in any other way than by contrast to black, which has historically been the default role of black life in a nation of “freedom and liberty for all.”

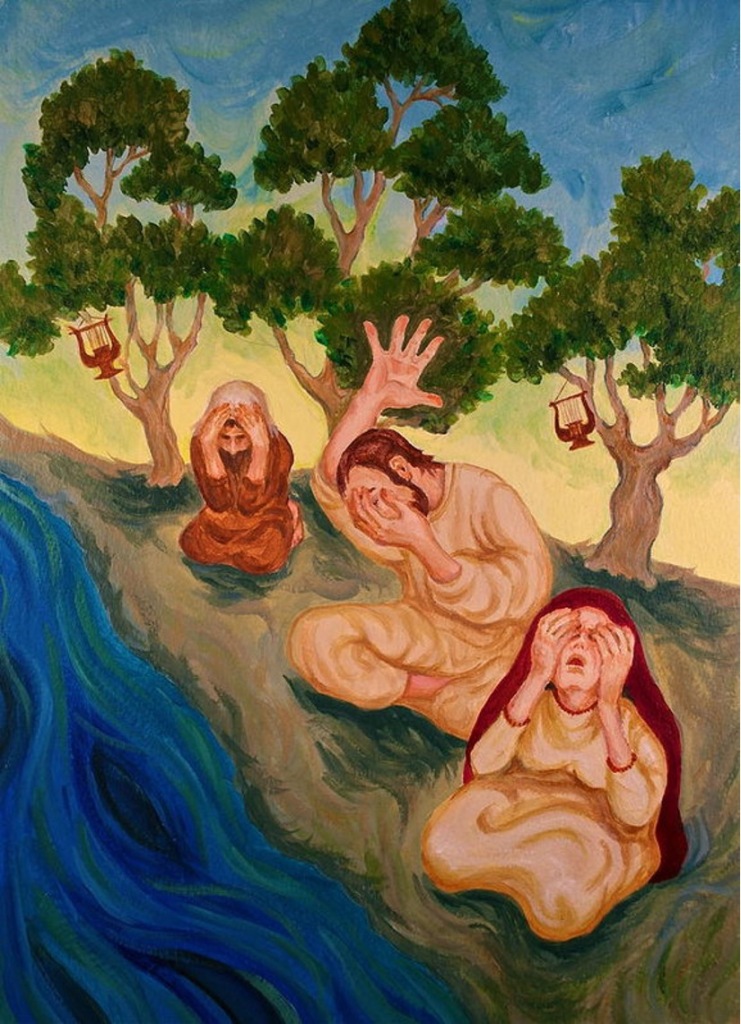

That withstanding, the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. yet remains in the Black social gospel interplay between religion, morality, law, and politics, summed up by the claim that justice is what love looks like in public.

—————————————————————

Dr. Williams received his Ph.D. in Christian ethics at Fuller Theological Seminary in 2011. Dr. Reggie Williams book Bonhoeffer’s Black Jesus: Harlem Renaissance Theology and an Ethic of Resistance (Baylor University Press, 2014) was selected as a Choice Outstanding Title in 2015, in the field of religion. The book is an analysis of exposure to Harlem Renaissance intellectuals, and worship at Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist on the German pastor and theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, during his year of post-doctoral study at Union Seminary in New York, 1930-31. Dr. Williams’ research interests include Christological ethics, theological anthropology, Christian social ethics, the Harlem Renaissance, race, politics and black church life. His current work is an examination of the field of Christian ethics through the lens of Black studies.

______________________________

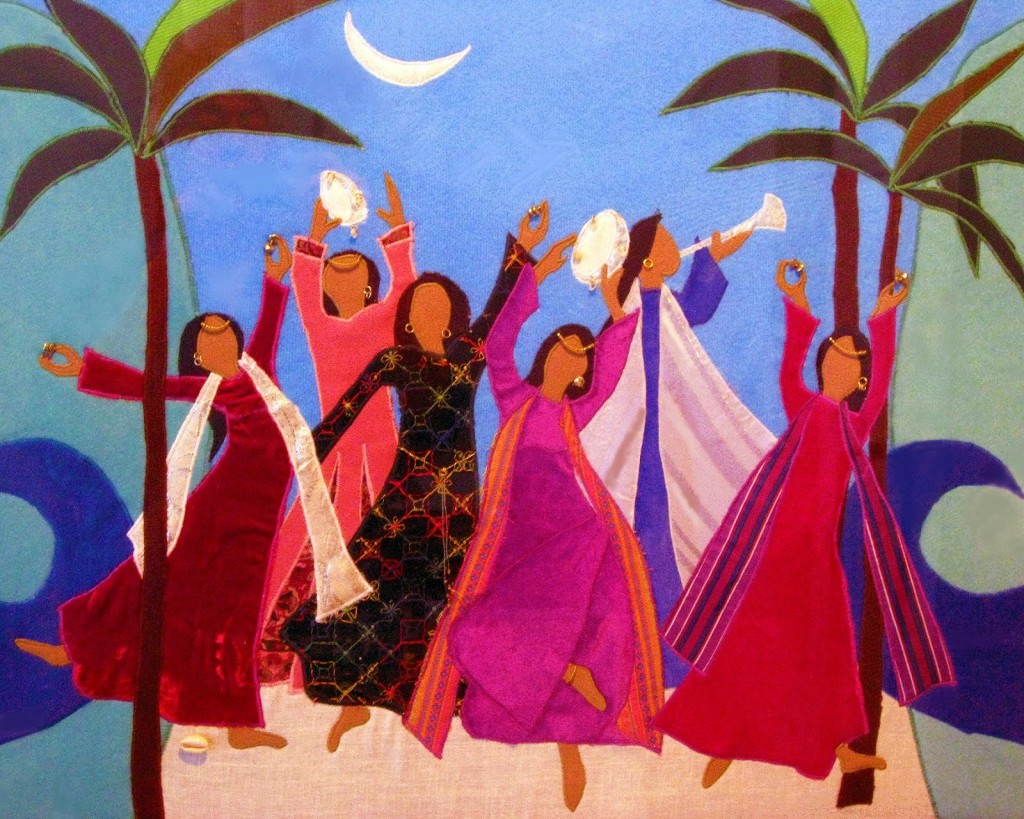

The Albert “Pete” Pero, Jr. and Cheryl Stewart Pero Center for Intersectionality Studies is hosting a special event on Monday, January 15, 2024 starting at 12pm CDT. Our annual Martin Luther King, Jr. Celebration, (click here to register) it will begin with some worship and praise, be followed by a light reception, which will then lead into a showing of the short film Otis’s Dream. The afternoon will then end with a panel discussion with. Rev. Dr. Joanne Marie Terrell and Dr. Christopher D. Ringer from Chicago Theological Seminary and the Rev. Honorable William “Bill” Hall, Alderman of Chicago’s 6th Ward and Pastor of St. James Community Church.